What Animals Are In The Canidae Family

| Canids Temporal range: Late Eocene-Holocene[one] : vii (37.8 Ma-present) | |

|---|---|

| | |

| ten of the 13 extant canid genera | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Form: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Suborder: | Caniformia |

| Family unit: | Canidae Fischer de Waldheim, 1817[2] |

| Blazon genus | |

| Canis Linnaeus, 1758 | |

| Subfamilies and extant genera | |

| |

Canidae (;[3] from Latin, canis, "dog") is a biological family of dog-like carnivorans, colloquially referred to equally dogs, and constitutes a clade. A member of this family is also called a canid ().[4] At that place are 3 subfamilies constitute within the canid family unit, which are the extinct Borophaginae and Hesperocyoninae, and the extant Caninae.[5] The Caninae are known as canines,[6] and include domestic dogs, wolves, foxes, coyotes and other extant and extinct species.

Canids are found on all continents except Antarctica, having arrived independently or accompanied human being beings over extended periods of fourth dimension. Canids vary in size from the 2-metre-long (vi.half dozen ft) grey wolf to the 24-centimetre-long (ix.4 in) fennec fox. The body forms of canids are similar, typically having long muzzles, upright ears, teeth adapted for not bad bones and slicing flesh, long legs, and bushy tails. They are mostly social animals, living together in family units or minor groups and behaving cooperatively. Typically, merely the dominant pair in a group breeds, and a litter of young are reared annually in an underground den. Canids communicate past odor signals and vocalizations. 1 canid, the domestic canis familiaris, originated from a symbiotic relationship with Upper Paleolithic humans and today remains one of the near widely kept domestic animals.

Taxonomy [edit]

In the history of the carnivores, the family unit Canidae is represented by the two extinct subfamilies designated as Hesperocyoninae and Borophaginae, and the extant subfamily Caninae.[five] This subfamily includes all living canids and their most recent fossil relatives.[1] All living canids as a group form a dental monophyletic relationship with the extinct borophagines, with both groups having a bicuspid (two points) on the lower carnassial talonid, which gives this tooth an additional ability in mastication. This, together with the development of a distinct entoconid cusp and the broadening of the talonid of the beginning lower molar, and the corresponding enlargement of the talon of the upper first tooth and reduction of its parastyle distinguish these belatedly Cenozoic canids and are the essential differences that identify their clade.[1] : p6

The cat-like feliformia and dog-like caniforms emerged inside the Carnivoramorpha around 45–42 Mya (1000000 years ago).[7] The Canidae first appeared in North America during the Belatedly Eocene (37.viii-33.ix Mya). They did not reach Eurasia until the Miocene or to South America until the Late Pliocene.[1] : vii

Phylogenetic relationships [edit]

This cladogram shows the phylogenetic position of canids within Caniformia, based on fossil finds:[1]

Evolution [edit]

The Canidae today includes a diverse group of some 34 species ranging in size from the maned wolf with its long limbs to the curt-legged bush dog. Modern canids inhabit forests, tundra, savannahs, and deserts throughout tropical and temperate parts of the earth. The evolutionary relationships between the species have been studied in the past using morphological approaches, but more than recently, molecular studies have enabled the investigation of phylogenetics relationships. In some species, genetic difference has been suppressed by the high level of gene flow between dissimilar populations and where the species have hybridized, large hybrid zones exist.[8]

Eocene epoch [edit]

Carnivorans evolved after the extinction of the non-avian dinosaurs 66 million years ago. Around 50 million years ago, or earlier, in the Paleocene, the carnivorans carve up into ii main divisions: caniforms (dog-like) and feliforms (cat-like). Past xl Mya, the first identifiable member of the dog family unit had arisen. Named Prohesperocyon wilsoni, its fossilized remains take been found in what is at present the southwestern role of Texas. The chief features which identify it every bit a canid include the loss of the upper third molar (office of a trend toward a more shearing bite), and the structure of the middle ear which has an enlarged bulla (the hollow bony structure protecting the delicate parts of the ear). Prohesperocyon probably had slightly longer limbs than its predecessors, and also had parallel and closely touching toes which differ markedly from the splayed arrangements of the digits in bears.[9]

The canid family soon subdivided into three subfamilies, each of which diverged during the Eocene: Hesperocyoninae (about 39.74–15 Mya), Borophaginae (about 34–ii Mya), and Caninae (most 34–0 Mya). The Caninae are the only surviving subfamily and all present-day canids, including wolves, foxes, coyotes, jackals, and domestic dogs. Members of each subfamily showed an increase in body mass with fourth dimension and some exhibited specialized hypercarnivorous diets that fabricated them prone to extinction.[10] : Fig. 1

Oligocene epoch [edit]

By the Oligocene, all three subfamilies of canids (Hesperocyoninae, Borophaginae, and Caninae) had appeared in the fossil records of North America. The primeval and near primitive branch of the Canidae was the Hesperocyoninae lineage, which included the coyote-sized Mesocyon of the Oligocene (38–24 Mya). These early canids probably evolved for the fast pursuit of prey in a grassland habitat; they resembled modern viverrids in appearance. Hesperocyonines eventually became extinct in the middle Miocene. One of the early members of the Hesperocyonines, the genus Hesperocyon, gave rise to Archaeocyon and Leptocyon. These branches led to the borophagine and canine radiations.[11]

Miocene epoch [edit]

Around 9–10 mya during the Late Miocene, the Canis, Urocyon, and Vulpes genera expanded from southwestern North America, where the canine radiation began. The success of these canines was related to the development of lower carnassials that were capable of both mastication and shearing.[xi] Around 8 Mya, the Beringian land bridge allowed members of the genus Eucyon a means to enter Asia and they connected on to colonize Europe.[12]

Pliocene epoch [edit]

During the Pliocene, around iv–5 Mya, Canis lepophagus appeared in North America. This was small and sometimes coyote-like. Others were wolf-similar in characteristics. C. latrans (the coyote) is theorized to have descended from C. lepophagus.[13]

The formation of the Isthmus of Panama, virtually 3 Mya, joined Southward America to North America, allowing canids to invade South America, where they diversified. Withal, the most recent common ancestor of the Southward American canids lived in N America some 4 Mya and more ane incursion across the new country span is likely. One of the resulting lineages consisted of the gray play a trick on (Urocyon cinereoargentus) and the now-extinct dire wolf (Aenocyon dirus). The other lineage consisted of the then-called South American endemic species; the maned wolf (Chrysocyon brachyurus), the short-eared dog (Atelocynus microtis), the bush domestic dog (Speothos venaticus), the crab-eating fox (Cerdocyon thous), and the South American foxes (Lycalopex spp.). The monophyly of this group has been established by molecular means.[12]

Pleistocene epoch [edit]

During the Pleistocene, the North American wolf line appeared, with Canis edwardii, clearly identifiable as a wolf, and Canis rufus appeared, possibly a directly descendant of C. edwardii. Effectually 0.eight Mya, Canis ambrusteri emerged in N America. A large wolf, it was found all over Due north and Cardinal America and was eventually supplanted by its descendant, the dire wolf, which then spread into South America during the Late Pleistocene.[fourteen]

By 0.3 Mya, a number of subspecies of the gray wolf (C. lupus) had developed and had spread throughout Europe and northern Asia.[15] The gray wolf colonized Due north America during the late Rancholabrean era beyond the Bering land bridge, with at to the lowest degree 3 separate invasions, with each one consisting of i or more different Eurasian gray wolf clades.[16] MtDNA studies have shown that there are at least four extant C. lupus lineages.[17] The dire wolf shared its habitat with the gray wolf, but became extinct in a large-scale extinction event that occurred around 11,500 years ago. It may have been more of a scavenger than a hunter; its molars announced to be adapted for burdensome bones and it may have gone extinct every bit a issue of the extinction of the big herbivorous animals on whose carcasses information technology relied.[fourteen]

In 2015, a study of mitochondrial genome sequences and whole-genome nuclear sequences of African and Eurasian canids indicated that extant wolf-similar canids accept colonized Africa from Eurasia at least five times throughout the Pliocene and Pleistocene, which is consistent with fossil evidence suggesting that much of African canid fauna multifariousness resulted from the immigration of Eurasian ancestors, likely coincident with Plio-Pleistocene climatic oscillations between barren and humid weather. When comparing the African and Eurasian golden jackals, the report concluded that the African specimens represented a distinct monophyletic lineage that should be recognized equally a separate species, Canis anthus (African golden wolf). According to a phylogeny derived from nuclear sequences, the Eurasian aureate jackal (Canis aureus) diverged from the wolf/coyote lineage 1.9 Mya, but the African aureate wolf separated ane.three Mya. Mitochondrial genome sequences indicated the Ethiopian wolf diverged from the wolf/coyote lineage slightly prior to that.[18] : S1

Characteristics [edit]

Wild canids are plant on every continent except Antarctica, and inhabit a wide range of different habitats, including deserts, mountains, forests, and grasslands. They vary in size from the fennec fox, which may be as footling as 24 cm (9.4 in) in length and weigh 0.6 kg (1.iii lb),[19] to the gray wolf, which may be up to 160 cm (v.2 ft) long, and can weigh up to 79 kg (174 lb).[xx] Only a few species are arboreal—the gray play a trick on, the closely related island fox[21] and the raccoon dog habitually climb trees.[22] [23] [24]

All canids have a similar bones form, as exemplified by the grayness wolf, although the relative length of muzzle, limbs, ears, and tail vary considerably between species. With the exceptions of the bush-league canis familiaris, the raccoon dog and some dog breeds, canids have relatively long legs and lithe bodies, adapted for chasing prey. The tails are bushy and the length and quality of the pelage vary with the season. The cage portion of the skull is much more elongated than that of the cat family. The zygomatic arches are broad, in that location is a transverse lambdoidal ridge at the rear of the cranium and in some species, a sagittal crest running from forepart to back. The bony orbits effectually the center never form a complete band and the auditory bullae are smooth and rounded.[25] Females accept iii to seven pairs of mammae.[26]

All canids are digitigrade, meaning they walk on their toes. The tip of the nose is always naked, as are the cushioned pads on the soles of the feet. These latter consist of a unmarried pad behind the tip of each toe and a more-or-less three-lobed key pad nether the roots of the digits. Hairs grow between the pads and in the Arctic fox, the sole of the pes is densely covered with hair at some times of the yr. With the exception of the 4-toed African wild dog (Lycaon pictus), five toes are on the forefeet, but the thumb (pollex) is reduced and does not reach the ground. On the hind feet are 4 toes, just in some domestic dogs, a fifth vestigial toe, known as a dewclaw, is sometimes present, but has no anatomical connection to the rest of the foot. The slightly curved nails are not retractile and more-or-less blunt.[25]

The penis in male person canids is supported by a bone called the baculum. Information technology likewise contains a construction at the base of operations called the bulbus glandis, which helps to create a copulatory tie during mating, locking the animals together for up to an 60 minutes.[27] Young canids are born blind, with their eyes opening a few weeks after birth.[28] All living canids (Caninae) have a ligament analogous to the nuchal ligament of ungulates used to maintain the posture of the caput and cervix with little active muscle exertion; this ligament allows them to conserve energy while running long distances following odor trails with their nose to the ground. However, based on skeletal details of the neck, at least some of the Borophaginae (such as Aelurodon) are believed to have lacked this ligament.[29]

Dentition [edit]

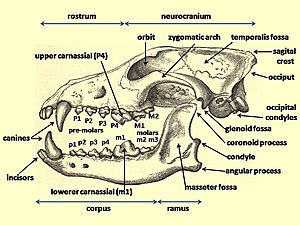

Diagram of a wolf skull with primal features labelled

Dentition relates to the arrangement of teeth in the oral cavity, with the dental annotation for the upper-jaw teeth using the upper-example letters I to denote incisors, C for canines, P for premolars, and M for molars, and the lower-example letters i, c, p and k to denote the mandible teeth. Teeth are numbered using one side of the mouth and from the front of the mouth to the dorsum. In carnivores, the upper premolar P4 and the lower molar m1 form the carnassials that are used together in a scissor-like action to shear the muscle and tendon of prey.[thirty]

Canids use their premolars for cutting and crushing except for the upper fourth premolar P4 (the upper carnassial) that is but used for cutting. They employ their molars for grinding except for the lower first molar m1 (the lower carnassial) that has evolved for both cutting and grinding depending on the canid'due south dietary adaptation. On the lower carnassial, the trigonid is used for slicing and the talonid is used for grinding. The ratio betwixt the trigonid and the talonid indicates a carnivore's dietary habits, with a larger trigonid indicating a hypercarnivore and a larger talonid indicating a more omnivorous diet.[31] [32] Because of its low variability, the length of the lower carnassial is used to provide an estimate of a carnivore'southward body size.[31]

A study of the estimated seize with teeth forcefulness at the canine teeth of a large sample of living and fossil mammalian predators, when adjusted for their trunk mass, establish that for placental mammals the bite force at the canines was greatest in the extinct dire wolf (163), followed among the modern canids by the four hypercarnivores that oft prey on animals larger than themselves: the African wild dog (142), the gray wolf (136), the dhole (112), and the dingo (108). The bite force at the carnassials showed a similar trend to the canines. A predator's largest casualty size is strongly influenced by its biomechanical limits.[33]

Most canids have 42 teeth, with a dental formula of: iii.ane.4.ii 3.1.4.iii . The bush dog has just one upper molar with ii below, the dhole has two above and two beneath. and the bat-eared fox has iii or four upper molars and 4 lower ones.[25] The molar teeth are stiff in most species, allowing the animals to fissure open bone to reach the marrow. The deciduous, or baby teeth, formula in canids is 3.i.3 3.i.3 , molars being completely absent-minded.[25]

Life history [edit]

[edit]

Almost all canids are social animals and live together in groups. In general, they are territorial or have a home range and sleep in the open, using their dens simply for convenance and sometimes in bad weather.[34] In most foxes, and in many of the truthful dogs, a male and female pair piece of work together to chase and to heighten their immature. Gray wolves and some of the other larger canids live in larger groups called packs. African wild dogs take packs which may consist of 20 to twoscore animals and packs of fewer than virtually 7 individuals may be incapable of successful reproduction.[35] Hunting in packs has the reward that larger prey items tin exist tackled. Some species form packs or live in small-scale family unit groups depending on the circumstances, including the blazon of available food. In most species, some individuals live on their own. Within a canid pack, at that place is a organisation of dominance so that the strongest, almost experienced animals atomic number 82 the pack. In most cases, the dominant male and female are the only pack members to breed.[36]

Cherry foxes barking in Pinbury Park, Gloucestershire, England.

Canids communicate with each other past scent signals, past visual clues and gestures, and by vocalizations such as growls, barks, and howls. In nearly cases, groups take a home territory from which they bulldoze out other conspecifics. The territory is marked by leaving urine scent marks, which warn trespassing individuals.[37] Social behavior is also mediated by secretions from glands on the upper surface of the tail near its root and from the anal glands,[36] preputial glands,[38] and supracaudal glands.[39]

Reproduction [edit]

A feral dog from Sri Lanka nursing her puppies

Canids as a grouping exhibit several reproductive traits that are uncommon amidst mammals equally a whole. They are typically monogamous, provide paternal intendance to their offspring, have reproductive cycles with lengthy proestral and dioestral phases and accept a copulatory tie during mating. They also retain adult offspring in the social group, suppressing the ability of these to breed while making utilize of the alloparental care they can provide to help raise the side by side generation of offspring.[40]

During the proestral period, increased levels of estradiol brand the female attractive to the male. There is a rise in progesterone during the estral phase when female person is receptive. Following this, the level of estradiol fluctuates and there is a lengthy dioestrous phase during which the female is pregnant. Pseudo-pregnancy ofttimes occurs in canids that have ovulated but failed to conceive. A period of anestrus follows pregnancy or pseudo-pregnancy, there being just one oestral period during each convenance flavour. Small and medium-sized canids mostly have a gestation period of fifty to sixty days, while larger species boilerplate 60 to 65 days. The time of twelvemonth in which the breeding season occurs is related to the length of day, as has been demonstrated in the example of several species that accept been translocated beyond the equator to the other hemisphere and experiences a vi-month shift of stage. Domestic dogs and certain pocket-size canids in captivity may come into oestrus more frequently, perhaps because the photoperiod stimulus breaks downwards nether atmospheric condition of artificial lighting.[xl]

The size of a litter varies, with from i to 16 or more than pups being born. The young are born minor, blind and helpless and require a long period of parental intendance. They are kept in a den, near frequently dug into the basis, for warmth and protection.[25] When the immature brainstorm eating solid food, both parents, and often other pack members, bring food back for them from the chase. This is most oftentimes vomited up from the adult'south breadbasket. Where such pack involvement in the feeding of the litter occurs, the breeding success rate is higher than is the case where females split from the grouping and rear their pups in isolation.[41] Young canids may take a year to mature and larn the skills they need to survive.[42] In some species, such as the African wild dog, male offspring usually remain in the natal pack, while females disperse as a group and join some other small group of the contrary sexual activity to form a new pack.[43]

Canids and humans [edit]

One canid, the domestic canis familiaris, entered into a partnership with humans a long fourth dimension agone. The canis familiaris was the first domesticated species.[44] [45] [46] [47] The archaeological record shows the first undisputed dog remains buried beside humans fourteen,700 years agone,[48] with disputed remains occurring 36,000 years ago.[49] These dates imply that the earliest dogs arose in the time of human hunter-gatherers and not agriculturists.[fifty] [51]

The fact that wolves are pack animals with cooperative social structures may have been the reason that the relationship adult. Humans benefited from the canid's loyalty, cooperation, teamwork, alertness and tracking abilities, while the wolf may take benefited from the use of weapons to tackle larger prey and the sharing of food. Humans and dogs may have evolved together.[52]

Amid canids, only the gray wolf has widely been known to casualty on humans.[53] [ page needed ] Yet, at least two records of coyotes killing humans have been published,[54] and at least two other reports of gilt jackals killing children.[55] Homo beings accept trapped and hunted some canid species for their fur and some, especially the greyness wolf, the coyote and the red play a trick on, for sport.[56] Canids such equally the dhole are now endangered in the wild considering of persecution, habitat loss, a depletion of ungulate prey species and manual of diseases from domestic dogs.[57]

See also [edit]

- Largest wild canids

- Canid hybrid

- Free-ranging dog

References [edit]

- ^ a b c d e Tedford, Richard; Wang, Xiaoming; Taylor, Beryl Eastward. (2009). "Phylogenetic systematics of the North American fossil Caninae (Carnivora: Canidae)" (PDF). Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 325: ane–218. doi:ten.1206/574.i. hdl:2246/5999. S2CID 83594819.

- ^ Fischer de Waldheim, Yard. 1817. Adversaria zoological. Memoir Societe Naturelle (Moscow) five:368–428. p372

- ^ Canidae. Dictionary.com. The American Heritage Stedman'southward Medical Dictionary. Houghton Mifflin Company. http://dictionary.reference.com/browse/Canidae (accessed: 16 February 2009).

- ^ Wang & Tedford 2008, pp. 181.

- ^ a b Miklosi, Adam (2015). Dog Behaviour, Evolution, and Cognition. Oxford Biology (2nd ed.). Oxford Academy Printing. pp. 103–107. ISBN978-0199545667.

- ^ Wang & Tedford 2008, pp. 182.

- ^ Flynn, John J.; Wesley-Hunt, Gina D. (2005). "Phylogeny of the Carnivora: Basal Relationships Among the Carnivoramorphans, and Cess of the Position of 'Miacoidea' Relative to Carnivora". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 3: 1–28. doi:10.1017/s1477201904001518. S2CID 86755875.

- ^ Wayne, Robert Yard. "Molecular evolution of the canis familiaris family". Retrieved 27 May 2014.

- ^ Wang, Xiaoming (2008). "How Dogs Came to Run the World". Natural History Magazine. Vol. July/August. Retrieved 24 May 2014.

- ^ Van Valkenburgh, B.; Wang, 10.; Damuth, J. (October 2004). "Cope'due south Rule, Hypercarnivory, and Extinction in North American Canids". Science. 306 (#5693): 101–104. Bibcode:2004Sci...306..101V. doi:x.1126/science.1102417. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 15459388. S2CID 12017658.

- ^ a b Martin, L.D. 1989. Fossil history of the terrestrial carnivora. Pages 536–568 in J.L. Gittleman, editor. Carnivore Behavior, Ecology, and Evolution, Vol. ane. Comstock Publishing Associates: Ithaca.

- ^ a b Perini, F. A.; Russo, C. A. 1000.; Schrago, C. G. (2010). "The evolution of Southward American endemic canids: a history of rapid diversification and morphological parallelism". Periodical of Evolutionary Biological science. 23 (#two): 311–322. doi:10.1111/j.1420-9101.2009.01901.x. PMID 20002250. S2CID 20763999.

- ^ Nowak, R.M. 1979. North American 4th Canis. Monograph of the Museum of Natural History, University of Kansas half-dozen:1 – 154.

- ^ a b Larson, Robert. "Wolves, coyotes and dogs (Genus Canis)". The Midwestern United States 16,000 years ago. Illinois State Museum. Retrieved 7 June 2014.

- ^ Nowak, R. 1992. "Wolves: The great travelers of evolution". International Wolf 2 (#four):3 – vii.

- ^ Chambers, S. M.; Fain, South. R.; Fazio, B.; Amaral, K. (2012). "An account of the taxonomy of North American wolves from morphological and genetic analyses". North American Beast. 77: 1–67. doi:x.3996/nafa.77.0001.

- ^ Gaubert, P.; Bloch, C.; Benyacoub, South.; Abdelhamid, A.; Pagani, P.; et al. (2012). "Reviving the African Wolf Canis lupus lupaster in Northward and West Africa: A Mitochondrial Lineage Ranging More than than 6,000 km Wide". PLOS ONE. 7 (#8): e42740. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...742740G. doi:ten.1371/journal.pone.0042740. PMC3416759. PMID 22900047.

- ^ Koepfli, Klaus-Peter; Pollinger, John; Godinho, Raquel; Robinson, Jacqueline; Lea, Amanda; Hendricks, Sarah; Schweizer, Rena M.; Thalmann, Olaf; Silva, Pedro; Fan, Zhenxin; Yurchenko, Andrey A.; Dobrynin, Pavel; Makunin, Alexey; Cahill, James A.; Shapiro, Beth; Álvares, Francisco; Brito, José C.; Geffen, Eli; Leonard, Jennifer A.; Helgen, Kristofer Yard.; Johnson, Warren Eastward.; o'Brien, Stephen J.; Van Valkenburgh, Blaire; Wayne, Robert K. (2015). "Genome-wide Evidence Reveals that African and Eurasian Gilt Jackals Are Distinct Species". Electric current Biology. 25 (#sixteen): 2158–65. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2015.06.060. PMID 26234211.

- ^ Marc Tyler Nobleman (2007). Foxes. Marshall Cavendish. p. 35. ISBN978-0-7614-2237-2.

- ^ Heptner, V. G.; Naumov, N. P. (1998), Mammals of the Soviet Union Vol. II Part 1a, Sirenia and Carnivora (Ocean cows; Wolves and Bears), Science Publishers, Inc. USA., pp. 166–176, ISBN one-886106-81-9

- ^ "ADW: Urocyon littoralis: Information". Animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu. 28 November 1999. Retrieved 12 June 2012.

- ^ Kauhala, K.; Saeki, M. (2004). Raccoon Dog«. Canid Species Accounts. IUCN/SSC Canid Specialist Group. Pridobljeno 15 April 2009.

- ^ Ikeda, Hiroshi (August 1986). "Old dogs, new tricks: Asia's raccoon domestic dog, a venerable fellow member of the canid family is pushing into new frontiers". Natural History. 95 (#8): forty, 44.

- ^ "Raccoon dog – Nyctereutes procyonoides. WAZA – Globe Association of Zoos and Aquariums". Archived from the original on 10 April 2015. Retrieved 30 Baronial 2011.

- ^ a b c d e Mivart, St. George Jackson (1890). Dogs, Jackals, Wolves, and Foxes: A Monograph of the Canidae. London : R.H. Porter : Dulau. pp. fourteen–xxxvi.

- ^ Ronald M. Nowak (2005). Walker's Carnivores of the Earth. JHU Press. ISBN978-0-8018-8032-two.

- ^ Ewer, R. F. (1973). The Carnivores. Cornell University Printing. ISBN978-0-8014-8493-iii.

- ^ Macdonald, D. (1984). The Encyclopedia of Mammals. New York: Facts on File. p. 57. ISBN978-0-87196-871-five.

- ^ Wang & Tedford 2008, pp. 97–98.

- ^ Wang & Tedford 2008, pp. 74.

- ^ a b Sansalone, Gabriele; Bertè, Davide Federico; Maiorino, Leonardo; Pandolfi, Luca (2015). "Evolutionary trends and stasis in carnassial teeth of European Pleistocene wolf Canis lupus (Mammalia, Canidae)". Quaternary Science Reviews. 110: 36–48. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2014.12.009.

- ^ Cherin, Marco; Bertè, Davide Federico; Sardella, Raffaele; Rook, Lorenzo (2013). "Canis etruscus (Canidae, Mammalia) and its role in the faunal assemblage from Pantalla (Perugia, central Italia): comparing with the Tardily Villafranchian large carnivore social club of Italia". Bollettino della Società Paleontologica Italiana. 52 (#ane): 11–18.

- ^ Wroe, Southward.; McHenry, C.; Thomason, J. (2005). "Bite gild: Comparative bite force in big biting mammals and the prediction of predatory behaviour in fossil taxa". Proceedings of the Purple Guild B: Biological Sciences. 272 (#1563): 619–25. doi:10.1098/rspb.2004.2986. PMC1564077. PMID 15817436.

- ^ Harris, Stephen; Yalden, Derek (2008). Mammals of the British Isles (4th revised ed.). Mammal Club. p. 413. ISBN978-0-906282-65-6.

- ^ McConnell, Patricia B. (31 August 2009). "Comparative canid behaviour". The other terminate of the leash . Retrieved 12 June 2014.

- ^ a b "Canidae: Coyotes, dogs, foxes, jackals, and wolves". Animal Diverseness Spider web. University of Michigan. Retrieved 13 June 2014.

- ^ Nowak, R. M.; Paradiso, J. L. 1983. Walker'south Mammals of the World. Baltimore, Maryland: The Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-2525-3.

- ^ Van Heerden, Joseph. "The role of integumental glands in the social and mating behaviour of the hunting dog Lycaon pictus (Temminck, 1820)." (1981).

- ^ Play tricks, Michael W., and James A. Cohen. "Canid communication." How animals communicate (1977): 728-748.

- ^ a b Asa, Cheryl Due south.; Valdespino, Carolina; Carbyn, Ludwig Due north.; Sovada, Marsha Ann, eds. (2003). A review of Small Canid Reproduction: in The Swift Fox: Environmental and Conservation of Swift Foxes in a Irresolute Globe. Academy of Regina Press. pp. 117–123. ISBN978-0-88977-154-3.

- ^ Jensen, Per, ed. (2007). The Behavioural Biology of Dogs. CABI. pp. 158–159. ISBN978-1-84593-188-nine.

- ^ Voelker, W. 1986. The Natural History of Living Mammals. Medford, New Bailiwick of jersey: Plexus Publishing. ISBN 0-937548-08-1

- ^ "Lycaon pictus". Beast Info: Endangered animals of the earth. 26 November 2005. Retrieved 11 June 2014.

- ^ Larson G, Bradley DG (2014). "How Much Is That in Dog Years? The Advent of Canine Population Genomics". PLOS Genetics. 10 (#1): e1004093. doi:10.1371/periodical.pgen.1004093. PMC3894154. PMID 24453989.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - ^ Larson G (2012). "Rethinking dog domestication by integrating genetics, archæology, and biogeography". PNAS. 109 (#23): 8878–8883. Bibcode:2012PNAS..109.8878L. doi:10.1073/pnas.1203005109. PMC3384140. PMID 22615366.

- ^ "Domestication". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2016. Retrieved 26 May 2016.

- ^ Perri, Angela (2016). "A wolf in dog'southward clothing: Initial dog domestication and Pleistocene wolf variation". Journal of Archaeological Science. 68: 1–4. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2016.02.003.

- ^ Liane Giemsch, Susanne C. Feine, Kurt W. Alt, Qiaomei Fu, Corina Knipper, Johannes Krause, Sarah Lacy, Olaf Nehlich, Constanze Niess, Svante Pääbo, Alfred Pawlik, Michael P. Richards, Verena Schünemann, Martin Street, Olaf Thalmann, Johann Tinnes, Erik Trinkaus & Ralf W. Schmitz. "Interdisciplinary investigations of the late glacial double burial from Bonn-Oberkassel". Hugo Obermaier Lodge for Quaternary Research and Archaeology of the Stone Age: 57th Annual Meeting in Heidenheim, 7th – xi April 2015, 36-37

- ^ Germonpre, M. (2009). "Fossil dogs and wolves from Palaeolithic sites in Belgium, the Ukraine and Russia: Osteometry, ancient Dna and stable isotopes". Journal of Archaeological Scientific discipline. 36 (#2): 473–490. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2008.09.033.

- ^ Thalmann, O. (2013). "Consummate mitochondrial genomes of ancient canids advise a European origin of domestic dogs" (PDF). Science. 342 (#6160): 871–4. Bibcode:2013Sci...342..871T. doi:x.1126/science.1243650. PMID 24233726. S2CID 1526260.

- ^ Freedman, A. (2014). "Genome sequencing highlights the dynamic early history of dogs". PLOS Genetics. x (#1): e1004016. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1004016. PMC3894170. PMID 24453982.

- ^ Schleidt, Wolfgang G.; Shalter, Michael D. (2003). "Co-evolution of humans and canids: An alternative view of dog domestication: Homo homini lupus?" (PDF). Evolution and Cognition. 9 (1): 57–72. Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 Apr 2014.

- ^ Kruuk, H. (2002). Hunter and Hunted: Relationships between carnivores and people. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Academy Printing. ISBN0-521-81410-3.

- ^ "Coyote attacks: An increasing suburban problem" (PDF). San Diego County, California. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 Feb 2006. Retrieved nineteen August 2007.

- ^ "Canis aureus". Animal Diversity Web. Academy of Michigan. Retrieved 31 July 2007.

- ^ "Fox hunting worldwide". BBC News. 16 September 1999. Retrieved 16 June 2014.

- ^ Kamler, J.F.; Songsasen, N.; Jenks, G.; Srivathsa, A.; Sheng, L.; Kunkel, K. (2015). "Cuon alpinus". IUCN Ruby-red List of Threatened Species. 2015: due east.T5953A72477893. doi:10.2305/IUCN.U.k..2015-4.RLTS.T5953A72477893.en . Retrieved 11 November 2021.

Bibliography [edit]

- Wang, Xiaoming; Tedford, Richard H. (2008). Dogs:Their Fossil Relatives and Evolutionary History. Columbia Academy Press, New York. ISBN978-0-231-13529-0.

External links [edit]

| | Wikimedia Commons has media related to Canidae. |

- "Canidae". National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI).

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Canidae

Posted by: emerickthavisa.blogspot.com

0 Response to "What Animals Are In The Canidae Family"

Post a Comment